The Sarez Wild Cat

Conservation Programme

By C. Esmond Gay - Sarez Bengals - 2004

Sarah and I love Bengals with a passion… they’re mesmerising, captivating and charming cats. We chose to breed them for those very reasons - and also because at that time, they were the closest that we could feasibly get to the creatures that have always been my lifelong obsession… wild cats. But now our devotion to our pedigree felines has turned our lives full circle, as we share our home with, and strive to conserve the breathtaking wild ancestors of our domestic household pets.

The Bengal is a hybrid of the wild leopard cat and the domestic cat, the first of which are believed to have been bred in 1963, by an American named Jean Mill. She helped found the breed in order to stop the wild cat pet trade, and their senseless slaughter for their magnificent pelts. This lady hoped that the general public would become outraged at those wearing or selling fur coats… garments that looked exactly like their own pet Bengals - and in part she succeeded; wild cat poaching survives, but in Britain at least, fur coat wearers are demonised and are considered to be social outcasts - the thieves of beauty.

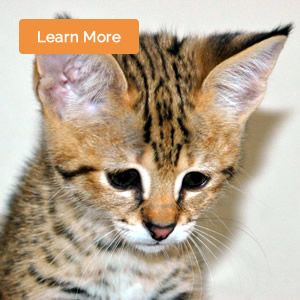

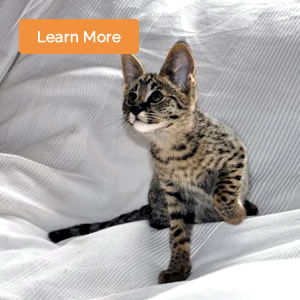

Because

of their recent wild forebears, the Bengal cat is an animal that is

both stunning and unique - one that not only duplicates the leopard’s

inherent beauty and intelligence, but also many other

characteristics, including their soft fur, their lean, athletic

bodies, their adoration for water, and even their stealthy gait.

Because

of their recent wild forebears, the Bengal cat is an animal that is

both stunning and unique - one that not only duplicates the leopard’s

inherent beauty and intelligence, but also many other

characteristics, including their soft fur, their lean, athletic

bodies, their adoration for water, and even their stealthy gait.

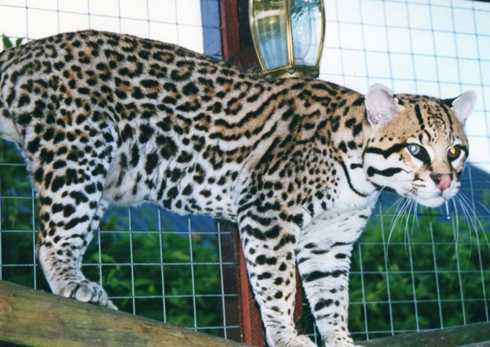

Ondine (Female Ocelot)

- Circa December 1995

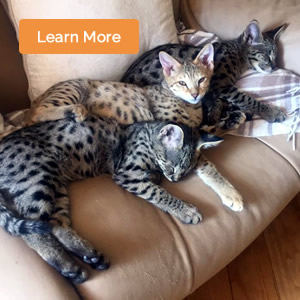

One of Our Servals -

Circa January 2003

And so in 1995, Sarah and I set up the Sarez Wild Cat Conservation Programme, but being private people, we didn’t want it to become a huge organisation - our aim was to simply do what we could to help a few threatened species of wild felines. To date, we have some endangered subspecies of leopard cat, African leopards, ocelots and servals, and we’d like to keep and help more species in the future.

We decided to fund it all ourselves on our estate, because we felt that charity status would strip away control and perhaps even force us to deviate from our original goals. And so everything we do for wild cats is paid for through the sale of our pedigree Bengal kittens - without them, we could not afford to do this work. And nothing about it is cheap; many big cats such as leopards, tigers and lions are offered to us with death sentences on their heads because, even though they are becoming scarce in the wild, they are quite common in captivity. However, only a few people can afford to spend around £60,000 housing them (each), and other regular expenses like food and vets bills, are equally terrifying!

Raj (Male African

Leopard) - 2000 to 2004

Out of all the wild cat species, ocelots have always been my favourite; they’re small, cute and outrageously beautiful. As a boy I’d see them in zoos and would stare at them, praying “please, one day…” So intense is my adoration for them, that when Sarah and I bought our first F1 Bengal, we named him Ocelot, because at the time we believed he was as close as we would ever get to owning one. But two years later we had to change his name to Occie to avoid confusion when my dream finally came true and we acquired real ocelots; a male called Quinton, and two females.

Ondine,

one of our hand-reared females, is one of my

most beloved of all our cats - so strong are my emotions for her that

a warm rush floods over me whenever I see her, or even think about

her. She came to us in late 1995 and I’ll never forget opening

the crate that she came in; I was so excited, but I expected her to

hiss and spit as we hadn’t hand-reared her. However, instead,

her huge round eyes looked up at me from her straw bed, she started

purring, and then she let me to pick her up and cuddle her. And

it’s been bliss ever since! She’s

so affectionate and possessive of me, so much so that Sarah can’t

really get close to me when Ondine

is on me or else she is liable to get nipped or at least, growled at!

Ondine,

one of our hand-reared females, is one of my

most beloved of all our cats - so strong are my emotions for her that

a warm rush floods over me whenever I see her, or even think about

her. She came to us in late 1995 and I’ll never forget opening

the crate that she came in; I was so excited, but I expected her to

hiss and spit as we hadn’t hand-reared her. However, instead,

her huge round eyes looked up at me from her straw bed, she started

purring, and then she let me to pick her up and cuddle her. And

it’s been bliss ever since! She’s

so affectionate and possessive of me, so much so that Sarah can’t

really get close to me when Ondine

is on me or else she is liable to get nipped or at least, growled at!

Esmond Gay &

Ondine (Female Ocelot) - 30th April 1996

When Sarah and I moved house in 1998, Ondine proved that her love for me is special. We needed time to build a new enclosure for her and our other ocelots at our new home, but we realised this would take several months as it had to be approved and licensed by our council and their vets. And so we asked a friend of ours to look after our ocelots as he had a private wildlife park. I was deeply distressed to lose Ondine for so long and I couldn’t visit her because this gentleman lived so far away and we couldn’t leave our other animals.

The enclosure took far longer to build than we had expected; we wanted it to be even more spectacular and far larger than their previous enclosure, and that took 7 months. I was so worried that Ondine would have forgotten me because she was adult, plus she had two others of her own kind with her, including her mate. And to make matters worse, the gentleman looking after them had warned me that all three ocelots had reverted to the wild and that neither he nor his staff could get near them - he told me not to expect too much.

Ondine (Female Ocelot)

- Circa March 1996

It’s an honour being loved so powerfully by one of nature’s most magnificent creations, by a cat whose innate wild instincts should tell her to avoid humans; yet Ondine’s love for me overrides them. It’s almost a “forbidden love”… and that type is always the strongest.

Quinton (Male Ocelot)

- Circa June 2001

Ondine (Female Ocelot)

- Circa July 2001

We also have servals and various subspecies of leopard cat in our conservation programme, and although their plight is not as dire as the ocelots, some are becoming threatened as their territories are destroyed.

Over the years, Sarah and I have cultivated good relationships with many of Britain’s top zoos and conversationalists, and they help us tremendously. It is rare for any pedigree cat breeder to be accepted into such circles, but they are aware that good intentions motivate us. Douglas Richardson, former curator of London Zoo, has been a great source of advice for us, whilst Terry Moore from the Cat Survival Trust has supported us from the outset of our breeding careers, and has been a vocal advocate of ours. His charity rescues Britain’s unwanted wild cats, giving them a good home for life, and he conserves various species, most notably the fishing cat (no other organisation has bred more). Peter James from the Santago Rare Leopard Project also helps and guides us; he is a great inspiration due to his work with the astonishingly rare clouded leopards, snow leopards and Amur leopards.

Raj (Male African

Leopard) - September 2001

Our Bengals also help other wild cat conservationists. Dr. Andrew Kitchener, curator of the National Museums of Scotland studies our F1s to find out how two species can interbreed when there are many anatomical and genetic differences between them, and he hopes to use his findings to enlarge and diversify the gene pools of felid species that are facing imminent extinction. This work is important to science and conservation, so much so that there’s even a small section in the museum about Sarez and our hybridisation work.

I feel proud when I reflect upon how our lives have metamorphosed since our first Bengal cats entered our lives and changed it so drastically - and of the irony of it all; Sarah and I have been so inspired by a pedigree cat, that we use the income from the sale of their kittens, to help their own threatened wild forefathers…

And that’s how life should be - one species helping the survival of others…

C. Esmond Gay

Sarez Bengals

Copyright 2004 C. Esmond Gay

Dedicated to Ondine - my dream and inspiration

Retirement Addition (2008)

Sarah and I achieved a phenomenal amount during the 11 years that we bred Bengals and many of our accomplishments are still unsurpassed. We obsessively chased every one of our goals and ambitions and didn’t stop until we had succeeded. And everything we did was meticulous and done to perfectionist standards.

However, this entailed working up to 18 hours a day, 7 days a week, and with few breaks or holidays. In hindsight, we did too much too fast because the enormous stress that we put ourselves under, plus looking after hundreds of animals almost single-handedly, took its toll on us mentally, emotionally and physically. By 2004, Sarah and I were suffering from severe exhaustion and so reluctantly, we retired. We hoped to lead a quieter life in Latin America, living and working with their endangered cats.

Our larger wild felines went to wildlife parks, our rescued animals went to sanctuaries and private homes, whilst many of our Bengals and leopard cats went to Pauline and Frank Turnock of Gayzette Bengals - they look after and nurture our cats, and are expanding the breeding programme that we worked so hard to create.

I stay in regular contact with Pauline and Frank and offer them my support and advice on the Bengal and wild cats. I follow their achievements, and behind the scenes, I am there for them and for the beautiful cats that we once so proudly owned.

To

Sarah and me, our cats were more than just pets or breeding animals -

they were our family. And within the articles I wrote, my deeply

emotional descriptions of them and how they influenced our lives,

portrays just how powerfully I love them; and so naturally, I feel

terrible loss and miss them tremendously. However, I am grateful for

the 11 wonderful years that they graced our home, and for the honour

and privilege of being able to share part of my life with them…

and for the amazing memories that they’ve

left me with.

C. Esmond Gay